Evangelising “Christians Without Christ”: Mission Among Indigenous Portuguese in a Land of Cultural Christianity

Introduction

In the European context, “indigenous” refers not to tribal groups but to populations rooted in a shared geography and cultural-religious tradition. In Portugal, this is predominantly Roman Catholicism. Yet many Portuguese live detached from a living faith. Although 80% of the population identifies as Catholic (Census 2021), according to the Pew Research Center in 2017 only 35% are practicing while 48% attend religious services very occasionally.

Nevertheless, Portugal is one of the western European countries to which religion is considered more important, being the 8th from a list of 34, only surpassed by countries in central and eastern Europe. This constitutes a source of hope and opportunity for evangelisation.

From 15 countries of Western Europe, Portugal has the highest percentage of people currently Christian:

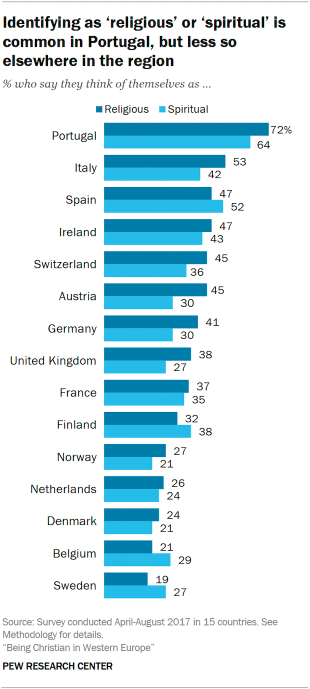

Furthermore: Portugal has the highest percentage of those who consider themselves religious or spiritual.

Fig. 3 - Source: Attitudes of Christians in Western Europe

This article explores the complexities of mission among these “indigenous Portuguese,” who grew up within cultural Christianity but may never have encountered the Gospel relationally or personally.

1. A “Naturally” Catholic Nation?

Portugal’s national identity is closely tied to Catholicism, dating back to the founding of the kingdom in 1179. Despite the 1911 Law on the Separation of Church and State (Marujo, 2024, p. 23), Catholic rituals continue to permeate public life — from toponymy and public holidays to local and popular celebrations.

Those who engage with Catholicism culturally rather than devotionally are commonly called “non-practicing Catholics.” Evert Van de Poll identifies them as “nominal” or “cultural Christians” (Van de Poll, 2022–2023, p. 61–86). This nominal religiosity in Portugal is often centred on Marian devotion — especially to the Lady of Fátima since 1917 — and overshadows Jesus Christ, making Him a marginal figure in many people's spirituality.

As shown below, the north and centre of Portugal are more Catholic, as well as Madeira and the Azores. The area of Lisbon and the south are less Catholic, and have more open space for evangelicals, other religions, or no religion.

Fig. 4 - Source - INE. Table created by Elsa Correia Pereira (Research ISUP - FCT).

2. Challenges to the Great (Co)Mission in Portugal

a) The Substitution of Christ by the Saints or other spiritualities

In popular Catholicism, saints, especially Mary, act as spiritual mediators. It is also important to acknowledge that, beyond cultural Catholicism, other religious expressions — such as African spiritualities, neo-pagan practices inspired by Celtic traditions, and local esoteric customs — have been emerging or reconfiguring themselves in some regions of the country, particularly in the north, contributing to an even more hybrid and syncretic religious landscape.

These religious practices often create a spiritual blindness that only prayer, fasting, and the work of the Holy Spirit can address[1] [2] .

b) The Evangelical Movement’s Recent History

Although Protestant communities have existed since the 19th century in our country, they were long regarded as foreign and in opposition to Catholicism. Under the Estado Novo regime, Evangelicals faced surveillance, social stigma, and even persecution. Legal recognition improved post-1976 as well as with the 2001 Religious Freedom Act, but social resistance remains.

The Portuguese Evangelical Alliance periodically conducts trusted research to understand the evolution of evangelisation, church planting, and church growth throughout the years. The research done so far was in the following years: 2016, 2020, 2023 and 2025. The picture below is from the last research and shows that the greatest percentage of evangelical leaders in Portugal (48%) says that converts in the last two years were reported to come mainly from a non-practising Catholic background.

c) Rising Secularism and the Privatisation of Faith

Alongside traditional religiosity, secularism has taken root, especially among youth. Faith is increasingly seen as a private, subjective matter. Grace Davie (1994) describes this phenomenon as “believing without belonging.” In Portugal, this hybrid religiosity includes believing without church involvement, belonging without believing (cultural identity), and — in fewer cases — both believing and belonging (active faith).

Linda Woodhead (2004) notes that cultural Christianity may also function as a form of resistance to societal change — a nostalgic clinging to identity rather than a transformative faith.

3. Opportunities for a Rooted Mission

a) The Need for Resonance

Hartmut Rosa (2024) introduces the concept of “resonance” — meaningful connections with others, the world, and the transcendent. Portuguese people often seek spiritual meaning but distrust religious institutions due to scandals and hierarchy. The evangelical message of a relational, living Jesus — shared through authentic testimonies, welcoming communities, and social justice — can meet this hunger in a context-sensitive way.

b) Rediscovering Jesus Within Portuguese Identity

Evangelisation should not dismantle culture but engage with it wisely. Many Gospel values — such as hospitality, generosity, and sacrifice — are already embedded in Portuguese customs. The mission is to reveal Christ as the fulfilment of these values, echoing Paul’s approach in Athens (Acts 17).

c) Church as Relational Community

Simple, relational, Bible-centred church expressions are resonating with Portuguese seekers. Evangelical communities with cultural sensitivity and active social engagement are growing. These churches must remain aware that many are observing from a distance — through live streams or occasional visits — and may not yet grasp evangelical language or norms. It is also important to mention that the growing presence of evangelical churches of Brazilian origin or influence has brought to our country a dynamic missionary spirit and expressive forms of spirituality that, while engaging for many, can create cultural tensions or perceptions of “religious importation” when not contextualised with sensitivity to the local reality.

d) Christian Migrants: A Courageous Witness in Public Spaces

The interaction between autochthonous evangelical churches and faith communities emerging from migration reveals complex dynamics of proximity and distance. In the case of migrant communities from the PALOP (Portuguese-speaking African Countries) and Brazil, the linguistic proximity to Portuguese believers may, in principle, facilitate more meaningful interactions. However, significant differences remain in liturgical expressions, musical styles, and ecclesial leadership models. Many of these churches nurture a spiritual experience characterised by a theology of resistance and hope, with strong references to the post-colonial and migratory context. Music — featuring rhythms and instruments characteristic of their cultures of origin — functions not only as an aesthetic expression but also as an identity marker. In migrant communities with distinct languages, particularly from Eastern Europe (notably Ukraine), and more recently from China and Southeast Asia, the evangelistic focus tends to remain within their own linguistic and cultural groups. Consequently, it is estimated that effective rapprochement between autochthonous and migrant communities will require the maturation of one or two generations more familiar with the Portuguese sociocultural context and simultaneously bearers of a hybrid identity.

Nevertheless, some forms of cooperation and coexistence are observable, albeit still occasional. The loan of facilities by Portuguese churches to migrant congregations has allowed worship services to be held at different times, creating a model of coexistence that, in some cases, results in a dual spiritual belonging: there are believers who attend the Portuguese church in the morning and the service of their community of origin in the afternoon (or vice versa).

“The loan of facilities by Portuguese churches to migrant congregations has allowed worship services to be held at different times, creating a model of coexistence that, in some cases, results in a dual spiritual belonging”

These practices reflect a functional articulation rather than full integration. On the other hand, many diaspora churches display a more audacious and visible presence in public spaces, promoting evangelistic initiatives in squares and on the streets—reviving urban mission practices that were also characteristic of Portuguese evangelicalism in previous decades. Initiatives in university contexts, such as those led by GBU (Grupo Bíblico Universitário) or Agape, further reflect more fluid interethnic experiences, in which migrant students actively engage in sharing their faith with Portuguese peers, thus contributing to new forms of spiritual and cultural exchange.

4. Final Reflections: Transforming Cultural Christianity into Mission Ground

To evangelise culturally Christian Portuguese is to walk alongside them — not attacking traditions but guiding hearts toward a living Christ. The goal is not to increase religiosity but to invite personal transformation.

So, we dare to propose some strategies:

a) Engage Cultural Christianity Respectfully

Recognise Christian cultural elements — holidays, moral values, biblical stories — as bridges for spiritual conversation, not obstacles. Arts can be used to help in building such connections and also to bring the Gospel to the public and online spaces wisely.

Fig. 6: OM (Operation Mobilization Portugal) has developed near the pilgrims in Fatima evangelisation and support projects. To know more, please listen here: https://www.facebook.com/share/v/19UBBRCCxC/

b) Avoid aggressive confrontation with Catholic Traditions

Rather than criticising Catholic rituals, demonstrate how the Gospel brings depth to heritage that many already value. For example, Bible studies at home and/or university groups work well with Catholics as they take a keen interest in reading the Bible for themselves.

Fig. 7: Photo of The Encontro Cristão. This initiative called “The Christian Gathering”, involves Christians from several denominations, namely Catholics, Protestants and some from evangelical free churches. It began in 2010 and has always had hundreds of participants. For more information please read here: “Vamos formar um belo mosaico”: mais de 1.100 cristãos de diferentes igrejas juntos em Sintra | Sete Margens

c) Promote Relational and Experiential Spirituality

Cultural Christianity can be ritualistic and impersonal. Evangelicals can offer an authentic, experiential faith centred on a personal relationship with Jesus.

d) Address Existential Needs

Many “cultural Christians” feel spiritual emptiness, especially during life crises. These are openings to present Jesus as relevant to modern struggles — from loneliness and anxiety to identity and hope.

e) Be Present at Transitional Moments

Life events — weddings, funerals, baptisms, religious festivals — are key opportunities for sensitive and meaningful engagement. Evangelicals should cultivate a pastoral presence in these contexts.

In a country where many believe but few know Jesus personally, the evangelical mission is not to introduce a foreign religion, but to reintroduce Christ to people, personally.

Connie Main Duarte is the General Secretary of the European Evangelical Alliance and a pastor at the Meeting Point, a Baptist church in Estoril, Portugal.

Elsa Correia Pereira is a researcher in Sociology of Religion, ISUP-FCT https://doi.org/10.54499/UI/BD/154276/2022

References

Davie, G. (1994). Religion in Britain Since 1945: Believing without Belonging. Blackwell Publishing.

Marujo, A. (coord.) (2024). Os caminhos da liberdade religiosa em Portugal. Lisboa: Assembleia da República, p. 23.

Rosa, H. (2024). Democracy Needs Religion. Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 57.

Van de Poll, E. (2022–2023). “Nominal, Fuzzy, and Cultural Christianity in Europe Today.” Journal of Post Christian Studies, Vol. 7, p. 61–86.

Woodhead, L. (2004). Christianity: