The Spirituality of Europe's Students

The values and beliefs of European students are often assumed rather than known. As a result the gospel of Jesus Christ is sometimes expressed in terms which make little sense to today’s European students. A research project conducted by IFES Europe in association with Redcliffe College has provoked some deep questions about the best way to evangelize this generation of European students.

Methodology

Questionnaire design is an exacting science and, rather than attempt to design our own questionnaire, the decision was taken to take advantage of the questions from the well-trusted European Values Study (EVS) a standardized tool which is used by many of Europe’s leading sociologists.

The European Values Study (EVS) is a large-scale, cross-national, and longitudinal survey research program on basic human values. It provides insights into the ideas, beliefs, preferences, attitudes, values and opinions of citizens all over Europe.

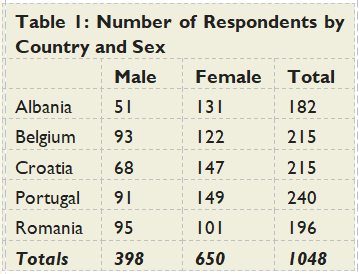

All IFES Europe movements were invited but only Albania, Belgium, Croatia, Portugal and Romania decided to engage with the research. Questions were selected from the EVS relating to religion, belief and spirituality. This enabled the IFES student volunteers to conduct the questionnaire in under ten minutes.

Results

A total of 1048 questionnaires were completed, approximately 200 per country. It proved more difficult to balance the number of male and female participants, the result of the greater proportion of females among university students in many European countries

The vast majority of the respondents (88% to be precise) were born in the seven years between 1987 and 1993, so at the time of the research were between 18 and 25 years of age, with a median age of 21.

The Important Things in Life

The first question in the survey asked respondents to say how important in their life were work, family, friends and acquaintances, leisure time, politics and religion. Analysis of those who responded that these were “very important” is set out in Table 2.

It is immediately apparent that in almost all the countries the family is considered to be the most important thing for students. In only one country (Belgium) does it not occupy the top position and in every other case over 85% of students say that family is very important to them. The second most important thing to students are their friends with this item appearing in the top three of every country but in most cases at a significantly lower level than the family.

Student Happiness

Perhaps the most striking finding of all came from the results of the question which asked about life satisfaction. Students were asked to rate on a ten-point scale: All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? As can be clearly seen from Figure 3 European students are on the whole very satisfied with their lives. The median score across the whole dataset is an 8 with 86% of students scoring between a 6 and a 10.

Believing without Belonging

The inclusion of a number of questions from the EVS on belief and religious participation enabled us to consider to what degree European students were “believing without belonging” as Grace Davie famously put it. One question asked: Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, about how often do you attend a religious service these days? The possible responses ranged from more than once a week to never or practically never and the results are displayed in Figure 4.

We also asked: how often do you pray outside of religious services? The possible responses ranged from every day to never. We found that, despite a lack of regular attendance at religious services many European students continue to pray (Figure 5).

Students were also asked about their belief in God: which of these statements comes closest to your beliefs: there is a personal God; there is some sort of spirit or life force; I don’t really know what to think; I don’t really think there is any sort of spirit, God or life force (Figure 6). Whilst belief in the divine is widespread, belief in a personal God is considerably lower. Nearly four times as many Belgian students believe in some sort of spirit or life force as in a personal God.

Religious or spiritual?

Another question asked: independently of whether you go to church or not, would you say you are: a religious person; not a religious person; a convinced atheist? As Figure 7 makes clear an extraordinarily high percentage of the students describe themselves as religious. Most strikingly over a third of Belgian students describe themselves as religious even though only 4% attend church on a weekly basis (Figure 4). The very low level of convinced atheists among students is also noteworthy, even in the most secularized of the countries in the analysis: Belgium.

The final question delved deeper into the issue of spirituality showing that European students are interested in spirituality (Fig. 8). Only a tiny minority have no interest, and most are somewhat or very interested. Even in Belgium half of the students had some interested in the sacred or supernatural.

Conclusion

Whilst differences were apparent between the countries some common patterns emerged. This led us to make three significant observations that were true for all:

The students in this study were largely satisfied with their lives.

The students in this study consider family and friends to be the most important things in their lives.

The students in this study were not always interested in religion but were interested in spirituality and the supernatural.

What follows is an attempt to reflect missiologically and theologically on the observations of this research.

Proposition 1: European students are largely satisfied with lives

This study found that European students are generally satisfied with their lives. This corroborates other studies such as that by Savage et al (2006), who found that British young people live by what they call a “happy midi-narrative”: their lives revolve around their friends being happy together in the here and now and overcoming problems through those friendships toward that end.

We might ask what the students who responded to our survey understand by “satisfied” but it seems to be very much focussed on enjoying life in the present.

Clearly this observation has huge missiological consequences

If European students are basically satisfied with their lives then many forms of evangelism which presuppose dissatisfaction with life will make little sense. This goes much further than a rethink of evangelistic materials or even of evangelism training but points to a need for a new theology of evangelism. This would involve effectively a change of missiological paradigm for many churches.

Whilst today’s young people are just as much in need of redemption as those of every other generation, our “missiological starting points” must posit answers to their spiritual questions not ours.

Their spiritual questions focus on the here and now. Films might continue to present fantasy eschatologies for entertainment purposes, but generally European young people look for a “realized” spirituality rather than one that focuses on the future.

Life must be celebrated and affirmed by churches and Christian organizations and seen to be so. So often young people see Christians as life-denying. Celebration should be rediscovered and reaffirmed as a core values of the Christian life.

Work, leisure and relationships must become the primary locus of spirituality, not only because it is here that most of life’s real questions are posed but also because these are the areas that are most in need of genuine redemption. It is here that the gospel may be seen to be “really” good news.

In sum, there is a need for a realized “whole life” spirituality that understands redemption as the transformation of all that is, by all that we have and are, so that Christ may be all in all (Col. 1:20; Rev. 21:1, 1 Cor. 15:24-28; 2 Peter 3:13).

“there is a need for a realized “whole life” spirituality that understands redemption as the transformation of all that is”

Proposition 2: European students consider family and friends to be the most important things in life

This study found that relationships with family and friends are the most important thing in the lives of European students,. It follows:

Evangelism and discipleship are so often focussed on the individual. We must learn to think once again in terms of the “oikos” or household, the primary community (or communities) to which we all belong and whose relationships are the most important thing for European young people. Zacchaeus’ repentance led not only to his “personal salvation” but also that of his whole family - “Today salvation has come to this house” (Luke 19:9). In European society where families are increasingly dysfunctional this message of “family salvation” is sorely needed.

A person’s relationships with parents, siblings and extended family are an inextricable part of who they are. The gospel must be communicated not only as good news for the individual, but “really” good news for the family. Further reflection is necessary on how practically the family might be honoured in our evangelism.

Our evangelism should be less propositional and more relational, telling the story of how we came to be part of family of Christ, and include practical teaching on how to live well as daughters and sons, sisters and brothers, friends and co-workers, etc.

As above, there is a need for fresh theological reflection in this case on the place of friendship in the ministry of Christ. Jesus chose to redefine his relationship with his disciples not as one of service to a master but in terms of friendship – “I have called you friends” (John 15:15).

Friendship is not friendliness. All too often “friendship evangelism” involves being friendly so as to gain the opportunity to share the Christian gospel. Not only is this increasingly seen to be false by marketing-savvy European youth, but it also does injury to the biblical understanding of friendship which is a relationship of trust where truth is spoken even when it is unpalatable (Proverbs 27:6).

Proposition 3: European students are not always interested in religion but are interested in spirituality and the supernatural.

Once again this observation suggests a need for further missiological reflection:

The secular worldview permeates the media, education and the public sphere to such a degree that we often assume people have no interest in spirituality. Nevertheless, a very significant proportion of European young people continue to believe in God and value spirituality even if they have no time for organized religion.

The presupposition that all European students are going to be secular humanists can lead to wrongheaded evangelistic approaches, self-censorship and the abandonment of the public sphere to the secular voices. Christian students must understand the secular worldview and be able to point out its weaknesses and presuppositions and to get actively involved in student politics.

There is a need for further reflection on why “spirituality” is seen as positive whilst “religion” is less so. Is this merely the spiritual aspect of the postmodern rejection of authoritative institutions or is there something more to it than that?

How can we speak the language of “spirituality” rather than “religion”? Is this not aspect of the theological paradigm shift we have already argued for, that our language, our way of talking about life and God, and even our “theological starting points” must respect the “starting points” of our audience, much in the way Jesus did with the woman at the well in John 4?

Prayer in some way shape or form continues to be a common practice of Europeans and even of European young people. Again further research is necessary but surely this is a potential bridge for dialogue.

Jim Memory

References

Savage, et al., Making Sense of Generation Y, Church House Publishing, London, 2006

This is an edited version of an article first published in Insight: A Journal for International Student Ministry in the UK, Friends International, Issue 10, 2013.