Perspective 4: Spanish Lessons

Spain has always had a rather love/hate relationship with the rest of Europe. Throughout its history Spain has allied with the Dutch, English and Germans against the French, with the French against the English, and found itself alone facing Germany, France and England. This could be said of many other countries but no Western European state, not even the United Kingdom, has been as staunchly isolationist as Spain.

Isolation

Spain’s national identity, forged under the Catholic Kings of Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492 when Jews, Muslims and later Protestants were expelled or converted has, for the best part of five centuries, been that of a bastion of Roman Catholicism.

This religious isolationism has played out politically and economically too, most recently, during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939-1975). Whilst initially favourable to the axis powers, Spain under Franco remained largely neutral during the Second World War, afterwards adopting a stict policy of autarky (self-sufficiency) and cutting off almost all international trade for the best part of twenty years. As a result Spain was the only major western European nation to be excluded from the Marshall Plan. Spain’s isolationism had already started to crumble long before the death of Franco in 1975 but it wasn’t until 1982 that Spain joined NATO and 1986 that Spain joined the EEC, the forerunner to the European Union.

Over the last thirty years Spain has been transformed into a modern liberal democracy and has reaped significant economic benefits. Tourism, construction and free-trade revitalized the economy and, since joining the EU, Spain has received more EU structural funds than any other member country. Membership of the Euro further fuelled the construction boom propelling Spanish earnings and GDP towards the European mean.

As a result, for more than a generation, Spaniards have been reflexively pro-European, apparently convinced of the truth of the dictum of José Ortega y Gasset, the philosopher and writer, that if “Spain is the problem, Europe the solution”. That is no longer the case. In five short years, the Spanish economic, political and social bubble has definitively burst.

The economic recession has left over six million Spaniards without work (27% of the working population) but it is among the young that the impact has been most dramatic. 57% of the under-25s are without work and facing emigration as the only alternative. And the austerity measures that have been required by the EU in order to support the Spanish economy have meant drastic cutbacks in public spending, turning Angela Merkel into a hate figure.

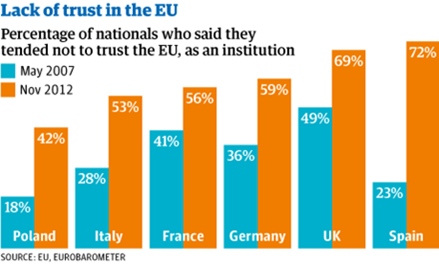

The degree to which Spanish trust in “Europe” has collapsed is well illustrated by the findings of a recent Eurobarometer study (Figure 1). As recently as 2007, the Spanish were one of the most pro-EU of the Europe’s larger countries. Less than five years later, Spaniards are found to be even more Eurosceptic than the British.

Migration

Spanish isolationism meant migration to Spain was rare until very recently. During the early 20th Century many Spaniards emigrated from Spain to Latin America and during the 60s and 70s to Germany, France and beyond, but migration to Spain was limited to wealthy Northern Europeans seeking a place to retire on the Costas. All this changed from the mid 90s. From under half-a-million foreign residents as recently as 1995, the boom in the Spanish economy and liberal migration policy saw that figure rise to nearly six million or 12% of the population by 2009 (Figure 2).

The influx was brought to a shuddering halt by the economic downturn and today many young Spaniards are emigrating once again. Spain´s population shrank by 200,000 during 2012. Whilst they are outraged that austerity measures imposed (as they see it) from Germany, the young seem reconciled to learning German to find work there. In Madrid and Barcelona there has been a 60% jump in the number of young Spaniards seeking to learn German (The Economist, June 1st 2013).

Even so, the last 15 years of migration to Spain have changed the country forever. After 500 years of isolationism, today one-in-eight citizens is a migrant. The Spanish church of the future will be an international church. The isolation of the past is a distant memory. A truly contextualized gospel for Spain will not only take into account Spanish history and culture, but also the impact of migration over the past 15 years.

The church

Previous generations faced with economic or political crises have turned to the Roman Catholic church for leadership, but the Spanish church is aligned with the governing right-leaning Partido Popular. Unlike Ireland or the US, the Spanish RC church has not (yet) suffered from scandals of sexual abuse however it is under attack for the generous tax arrangements it enjoys.

Most Spaniards, when asked about their religious affiliation, continue to identify with the RC church but have disassociated themselves from the church´s positions on human sexuality and reproduction. Because of its low fertility rate in recent decades, Spain is ageing rapidly. Having had 5.6 people of working age for every retired person in 1970, Spain has just 3.6 today. By 2050, the ratio will have deteriorated to 1.5, according to the OECD.

Religious isolationism is also a problem for the protestant and evangelical churches in Spain. Persecution during the time of Franco was followed by many decades when evangelical churches isolated themselves from the public sphere, except where public problems such as drug addiction and, more recently, migration came to them.

The economic crisis has changed this however. Not all evangelical churches wanted or felt capable of dealing with people with drug problems but opening a food bank has become more and more common. The vast majority of evangelical churches in Spain now have an official or unofficial distribution of food to the needy. Whereas in the early 2000s food hand-outs were generally to poor migrants, today many Spanish families are turning to the church for help, whether that is the food banks of the evangelical church or those of Caritas, the RC charity.

“Whereas in the early 2000s food hand-outs were generally to poor migrants, today many Spanish families are turning to the church for help”

The arrival of migrants has also had a marked impact on Spanish churches, particularly the arrival of significant numbers of Latinamerican and Romanian evangelicals. Some churches have become predominantly churches of migrants with just a small minority of nationals. Many more ethnic churches have appeared, Romanian churches but also new Spanish-speaking churches gathering believers from single nations despite their common language. Integration is an on-going challenge.

Esperanza para Europa

Faced with an aging population, failing trust in political and religious institutions, and economic stagnation, where can Spanish citizens turn for hope? The challenge for Spanish churches is to remain confident in the message of hope that is found in the gospel, to be what they were called to be, a people “from every tribe and tongue and people and nation” (Rev.5:9) will gather to worship and serve him.

As Tomas Sedlacek argues convincingly (see book review) this world´s only hope is in a return to the consumption-driven economic growth that got us into this mess. The churches of Spain, and across Europe must incarnate and communicate a different hope, one that solves the isolationism that beleaguers the soul of us all: our isolation from God and from each other. Europe is not the solution for the problem of Spain. The only hope for Spain; the only hope for Europe was, and is, and always shall be Jesus Christ.

Jim Memory, Redcliffe College